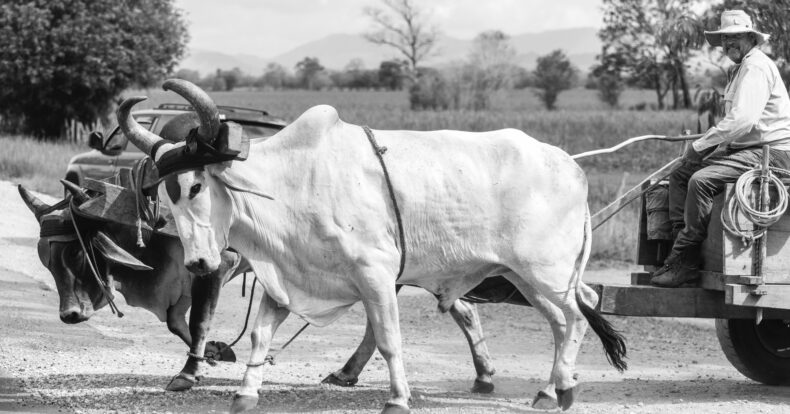

Sabaneros: regional identity

“Sabaneros” are a symbol of the identity of Guanacaste. They ride on horseback, tend the fields and their characteristic hat protects them from the sun of the plains and the rain. In all civic events, children and boys wear their sabanero costumes to honor this Costa Rican population. But where did the sabanero culture originate and why is it considered so important in Costa Rica? In this article, we will talk a little about the creation of this regional identity.

Identity was considered after World War II as the essence of an individual or an outstanding character shared by a group. However, as the years went by, the different racial and ethnic movements began to question this definition, which was static and essential. It was then taken for granted that identity is fluid, multiple, unstable, and very importantly, constructed.

Historical research on regions and regional identities has shown how histories and regional identities and regionalisms are the product of processes of construction of power discourses.

In the case of Costa Rica, the province of Guanacaste has been racialized as the mestizo region of the country and was imagined as a white and homogeneous nation. This was reinforced through school books and foreign travelers visiting Costa Rica. But it was in the 1930s when the images of popular Guanacaste culture began to show the “sabanero” as the official representation of the entire province, a product of the regional discourse that sought to unify the social classes into one.

According to the regionalist newspaper El Guanacaste in its column Letanías, the exemplary Guanacasteco had to be humble, without great desires, dominate his passions and eliminate hypocrisy; in addition, happiness had to be earned by his own means and always be satisfied with his life. On top of that, the Letanías column instructed the villagers to cultivate the land, to be good riders, to be educated people and to promote their folklore.

As the figure of the sabanero became a Guanacaste symbol, studies about it began to emerge. For Marc Edelman, the cult of the sabanero was created to stimulate the peasants to work on their haciendas, since it was the only way to keep the workers on their farms and overcome the crisis of the 1930s.

So yes, the figure of the sabanero is a Guanacaste symbol that has remained to this day with the same values and customs. We see him in national television series, in plays, in literature, in songs and even in commercials. But, we must ask ourselves, how much of our national and regional identity is natural and how much is forced?

Author: Mónica Gallardo for Sensorial Sunsets

Navigate articles